English View All Ceramics & Glass

English Ceramics

Pottery in England dates back to its Celtic past which has been proven by a multitude of excavations. Red clay was used until the 16th century. With the arrival of Dutch and German craftsmen, fleeing their homelands because of religious persecution, British pottery began to change. British tin-glazed earthenware was being manufactured in the 1660’s.

By the end of the 18th century, the term “delftware” referred to tin-glazed pottery, named after the tin-glazed pottery from the Netherlands, which it often copied. Tin glazing allowed objects to be decorated with colored pigments applied over a lead glaze and this made the pot opaque. English delftware is not the same as Dutch delftware. British delftware is harder and coarser than the softer, thinner Dutch variety. The glaze on English delftware is smoother but chips easily. The blue and white palette was most popular.

In the 1670s, John Dwight (1635-1703) was the first potter to solve the problem of producing stoneware. In 1672-3 he opened his factory, Fulham Pottery. He made brown, salt glazed Rhenish-style stoneware along with whitewares and red stoneware. Salt-glazed pottery has a granular “orange peel” texture. The factory remained in business for 300 years. Besides production being in three areas of London: Fulham, Lambeth and Mortlake; it was also in Staffordshire and Nottingham.

Staffordshire is not a factory, but is an area in England where there was an abundance of clay just a few feet underground. Within the area there were five towns: Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, Hanley, Tunstall and Longton. The area became known as the “Potteries”, where there were as many as four thousand kilns. The wares were attractive, affordable and extremely popular.

Creamware and pearlware were being made in Stafforsdshire from the 17th Century. If the clear glazed earthenware body is a cream color, it is called creamware. Three potters associated with the development of creamware are Thomas Astbury (1686-1743), Enoch Booth of Tunstall and Josiah Wedgwood (1730-1795). Wedgwood being the more well-known. Creamware was made for the next one hundred years. It could be finely molded or cut with precision and was relatively easy to underglaze in blue and overglaze with enamels. It was also made in Leeds.

Pearlware, also introduced by Wedgwood, had an iridescent look, which is attributable to the addition of cobalt oxide to the glaze. Pearlware could also be transfer printed. An example of this is the ubiquitous “Willow“ pattern.

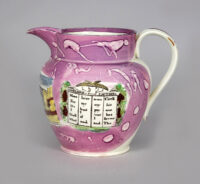

Pratt Ware is another type of pearlware. It is relief decorated and underglaze colored ware and was made from 1785 to 1840. It is similar to pearlware but it is known for strong bright colors like green, ochre, yellow, brown and blue. Forms included jugs, teapots and figures.

A fine white stoneware, called Ironstone china, was introduced in England early in the 19th century. It was patented by Charles James Mason (1791-1856) in 1813 under the name “Mason’s Patent Ironstone China”. There is no iron in ironstone, it’s not porcelain or from China. It’s so named because of its strength and durability. It was produced in Staffordshire and was relatively inexpensive because it was mass-produced. The colors are derived from Chinese rose medallion designs and Japanese Imari. Spode is another famous name in Staffordshire potteries. They made ceramic wares of the finest quality.

Josiah Spode (1733-1797) was responsible for developing the technique for underglaze transfer printing on pottery, the first being the “Willow” pattern. His son Josiah Spode II continued manufacturing after his father died. He developed Bone China and Felspar Porcelain, which is the forerunner of all modern English Bone China. Their pattern books show over 5000 designs.

The 18th and 19th centuries were exciting years for innovation of ceramic wares in Britain. There was much experimentation in trying to replicate Chinese porcelain. Kaolin, the major ingredient in true porcelain, had not yet been discovered in Cornwall and so English factories had to find alternate formulas. Porcelain manufacture in England was not subsidized by the government as Meissen in Germany, Sevres in France and Capodimonte in Italy were. English factories were on their own in establishing profitable business practices, which was difficult because there was an enormous amount of competition. Factories opened and closed if they weren’t producing up to the minute fashionable styles of quality with competitive pricing.

One of the ingredients of a substitute porcelain was bone ash. The use of bone ash was developed by the Bow works of Thomas Frye who was able to get bone from the slaughterhouses of Essex. But it was Josiah Spode who realized its potential and who actually coined the name bone china. Traditionally, English bone china was made from two parts of bone ash, one part of kaolin and one part china stone. By the 1790s, Spode was manufacturing excellent products of highest quality.

William Cookworthy (1705-1780) was the first person in Britain to actually discover how to make hard-paste porcelain and founded a factory in Plymouth. The early factories of importance were Chelsea, Vauxhall, Bow, St. James, Derby and Bristol. Worcester became a major manufacturer. It was founded in 1752 by Dr. John Wall and William Davis with investments from thirteen other partners. Originally they made exact copies of Chinese blue and white plates but turned to making original chinoiserie designs instead. They made sauce boats, vases, jugs, tureens but they specialized in teasets since their porcelain could withstand hot liquids without damage. Worcester became almost better than its Chinese counterparts and captured the English market. Worcester invented blue and white transfer printing in the 1750s. Since they weren’t hand painted, teasets were less expensive and every piece matched. Their quality was exceptional.

Thomas Flight, a London china dealer, bought the business in 1783 for his sons Joseph (1762-1838) and John (1766-1791). John Flight sold French porcelains in his London shop and persuaded Worcester to stop making blue and white and produce the latest French styles with high quality gilding instead. Martin Barr (1757-1813) joined the company a year later in 1792 and they traded as Flight and Barr. That became a very successful venture. Then in 1804 the name changed again and became Barr Flight and Barr and then in 1813, Flight Barr and Barr. The wealthy London customers returned to the fold and the nobility had diner services made with their family crests emblazoned on the porcelain. The quality of their wares was above reproach.

In the 1830s the Neo-Rococo style became popular with up and coming industrialists who now had more money than old established families. The demand for rich classical porcelain diminished and the Flight, Barr & Barr factory was resistant to change designs that had been so successful. Only the most adaptable and innovative porcelain factories survived. In 1840 the Flight, Barr and Barr factory joined forces with its former rival Chamberlain and between them they evolved new products and ideas which were to establish the Worcester Company in the Victorian Era.*

Other English factories: Lowestoft, Liverpool, Longton Hall, Plymouth and Bristol, Newhall, Caughley, Davenport, Ridgway, Spode and Copeland, Minton, Derby, Coalport, Swansea, Rockingham, etc.

Susan has a large selection of English porcelains. Browse the category. She’s sure there is something there for you.

*Museum of Royal Worcester https://www.museumofroyalworcester.org/learning/research/factories/flight-barr-partnerships/

755 North Main Street, Route 7

755 North Main Street, Route 7